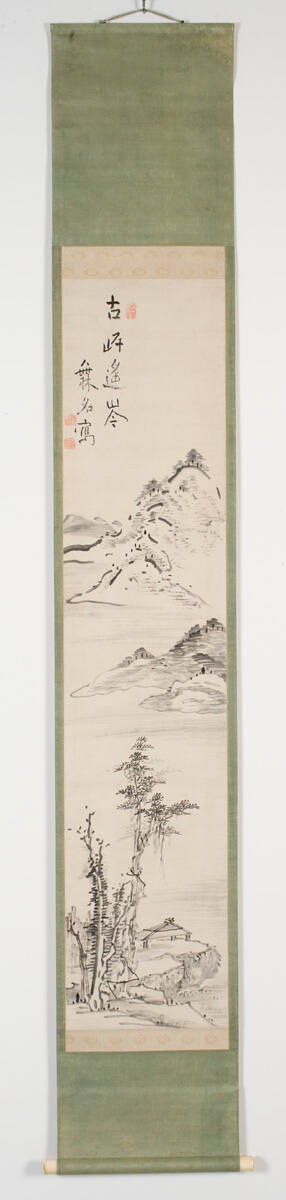

A Screen for the New Year: Pines and Plum Blossoms

Artist

Kano school

(Japanese, Edo period, 1615–1868)

Dateearly–mid 17th century

Mediummineral pigments, ink, and gold leaf on paper

Dimensions169.5 x 358 cm (66 3/4 x 140 15/16 in.)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineStoddard Acquisition Fund

Object number2012.97

Descriptionsix-panel folding screen; mineral pigments, ink, and gold leaf on paperThis rare screen is representative of the sophisticated elegance, energy and sumptuousness that appealed to Japanese noblemen and feudal lords in the early to mid-17th century. Created to be displayed in a dimly lit room in a castle during the New Year season, the screen features two enduring New Year’s symbols set against a gold foil background. The two motifs are dark, hardy evergreen pines that are emblematic of long life, dignity and virtue, and the first flowers of the lunar calendar year, delicate white plum blossoms, symbolic of new life.

During the 15th to mid-16th centuries, Kanō school artists were often commissioned by Zen abbots and feudal warlords to produce monochrome ink paintings with subjects such as Chinese landscapes with scholars, or tiger and dragon motifs. Then, during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Eitoku (1543-90) and his sons and students dramatized and expanded the Kanō school repertoire and painting-style. By the peaceful Edo period (1615-1868), when wealthy merchants also began to commission screens, Kanō school artists freely merged ink brushwork with the bright colors, patterning and seasonal references associated with traditional Japanese tastes. In this screen vertical and diagonal branches and soft pine boughs are contrasted with an undulating branch of white plum blossoms that dramatically winds across the screen surface, partly traced through the added depiction of lichen.

Folding screens are one of the most distinctive forms of Japanese art. Often serving to stop drafts in rooms or as windbreaks during outdoor festivities, they were called byōbu, “protection from the wind.” The format offered artists of different schools (i.e., Tosa, Kanō, Rimpa, ukiyo-e, Shijō, Nanga, Nihonga, etc.) the challenge to work on a monumental scale and to depict a variety of subjects.

Since their introduction to Japan from China and Korea during the 7th and 8th centuries, screens became indispensible for Japanese daily life—as symbols of power, aesthetic, flexible partitions of interior spaces, and expressions of personal taste. Traditional Japanese rooms are measured by their number of woven straw mats (tatami) on the floor. The rooms are enclosed by panels that slide on wooden tracks (fusuma). Folding screens vary in number of panels (ranging from 2 to 10). By simply changing a few furnishings and bringing in appropriate screens, rooms could be configured for different functions and activities. A pair of large six-panel screens could set the atmosphere for official ceremonies and celebrative banquets; smaller screens were often used for tea ceremonies or poetry gatherings. Screens were also used create intimate spaces suitable for sleeping, giving birth, or committing ritual suicide.

Label TextThis rare screen is representative of the sophisticated elegance, energy and sumptuousness that appealed to Japanese noblemen and feudal lords in the early to mid-17th century. Created to be displayed in a dimly lit room in a castle during the New Year season, the screen features two enduring New Year’s symbols set against a gold foil background. The two motifs are dark, hardy evergreen pines that are emblematic of long life, dignity and virtue, and the first flowers of the lunar calendar year, delicate white plum blossoms, symbolic of new life. During the 15th to mid-16th centuries, Kanō school artists were often commissioned by Zen abbots and feudal warlords to produce monochrome ink paintings with subjects such as Chinese landscapes with scholars, or tiger and dragon motifs. Then, during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Eitoku (1543-90) and his sons and students dramatized and expanded the Kanō school repertoire and painting-style. By the peaceful Edo period (1615-1868), when wealthy merchants also began to commission screens, Kanō school artists freely merged ink brushwork with the bright colors, patterning and seasonal references associated with traditional Japanese tastes. In this screen vertical and diagonal branches and soft pine boughs are contrasted with an undulating branch of white plum blossoms that dramatically winds across the screen surface, partly traced through the added depiction of lichen. Folding screens are one of the most distinctive forms of Japanese art. Often serving to stop drafts in rooms or as windbreaks during outdoor festivities, they were called byōbu, “protection from the wind.” The format offered artists of different schools (i.e., Tosa, Kanō, Rimpa, ukiyo-e, Shijō, Nanga, Nihonga, etc.) the challenge to work on a monumental scale and to depict a variety of subjects. Since their introduction to Japan from China and Korea during the 7th and 8th centuries, screens became indispensible for Japanese daily life—as symbols of power, aesthetic, flexible partitions of interior spaces, and expressions of personal taste. Traditional Japanese rooms are measured by their number of woven straw mats (tatami) on the floor. The rooms are enclosed by panels that slide on wooden tracks (fusuma). Folding screens vary in number of panels (ranging from 2 to 10). By simply changing a few furnishings and bringing in appropriate screens, rooms could be configured for different functions and activities. A pair of large six-panel screens could set the atmosphere for official ceremonies and celebrative banquets; smaller screens were often used for tea ceremonies or poetry gatherings. Screens were also used create intimate spaces suitable for sleeping, giving birth, or committing ritual suicide. ProvenanceErik Thomsen Gallery, New York, NY

On View

Not on viewUtagawa Kunisada I 歌川 国貞 (Toyokuni III 三代 豊国)

about 1836–1838